Today Nancy Espuche, the author of ‘Kardboard House,’ shares more of her and her son Lucas’s story.

Nancy and Lucas not only navigated the disease of addiction. Lucas, as an infant, developed pancreatitis and suffered from no diagnosis for a long time.

These two no-fault diseases impacted how they lived, yet you will hear many examples of the typical family questions and struggles when loving someone with an addiction.

Nancy shares powerful visuals of the disease’s impact on Lucas and herself.

To learn more about Nancy, her book, her training, visit her website: https://www.kardboardhouse.com

See full transcript below.

00:01

You’re listening to The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast, a place for real conversations with people who love someone with the disease of addiction. Now, here is your host, Margaret Swift Thompson.

Margaret 00:24

Welcome back today, Nancy will share some visuals that can offer different ways to understand this complex disease. Courage is magnificent to witness in Nancy’s open, honest, and vulnerable sharing of one of life’s most painful realities. When you lose someone to the disease of addiction, not to mention your child, is mind blowing. Let’s hear from Nancy.

00:54

The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast.

Margaret 01:05

When you think of his life was lived, you know, a very full for the 25 years he was here, it goes back to that this disease is more powerful than love, best intention. Education. It’s a combination of needing to surrender, which is so hard for people, whether on the family side or the side of the person with the disease.

Nancy 01:32

Letting go, one of the, letting go, surrendering. Whatever you want to call it, getting rid of those, those thorns that, you know, pluck you every day that say, I have to control this, I have to control this. I have I can do it. I know the best way, my way, let me or just taking over. And learning how to release that. And letting the world unfold and letting the universe do what it needs to do. In honor of every human being is I think what we’re really here to learn. But probably one of life’s most difficult lessons.

Margaret 02:22

Especially when the outcome is not what you ever imagined,

Nancy: No.

Margaret: was going to be the story of the people you love.

Nancy 02:29

And couldn’t, it wouldn’t even enter my consciousness that this was going to be part of my story and Lucas’ journey, it didn’t even exist. And that’s why it takes so long to, for family members. When it does start to rear its ugly head, your head spins too. It’s like, wait, is something happening here? Do I need to look at this not from the place that I’m sitting but from a whole other? Do I need to take an ariel view and go learn about this? Cannot imagine what happens to, I say this very lovingly, but I think mothers different than fathers. The people who show up in those rooms, 85% mothers, every one of them. And that’s not to minimize the impact of the father.

Margaret: No.

Nancy: But as a person who carries that child for nine months, and is seen often as the nurturer. That maternal instinct, that drive to protect is immeasurable. And as a mother, I couldn’t believe that I was, had a child who was hurting so deeply, and that I was hurting so deeply because of that.

Margaret 03:49

And the saying is always true. Hurt people hurt people. Never want to, never intend to. And I think it’s really important at this point to say when I say that in this situation. I don’t hold you nor Lucas responsible for any part of this no-fault disease. I would never. No matter the outcome of the story. I just mean that when we are so hurting, stuff comes out that hurts one another unintentionally.

Nancy 04:19

I agree with that. I do we lash it’s almost I think people that are hurt or at least I can speak for myself, my younger self. When I was hurting but didn’t want to look at my participation in the situation or the experience. And it was too scary to look at myself and too shameful I was too ashamed to look at myself. I lashed out. People lash out with no intention of wanting anybody to feel badly or to be hurtful. But it’s a knee jerk response I think until you get conscious.

Margaret 05:04

And what that speaks to for me and listening to that is your process of healing in recovery learning to look at our side of the street, learning to turn the mirror into us, learning our powerlessness and the need to surrender the people we love to something greater than us, because we can’t do that job for them.

Nancy 05:21

Right! We all have a very different perception of that when we’re first mothers, when we’re first when we first bring a child into the world, you know, not consciously even but we can mold them, shape them, you know, young children are malleable, and they’ll fallow my way. And, again, not with any conscious thought. I just by virtue of who we all are.

Margaret 05:43

As a mother of a youngster. Our kisses on their booboo made all the difference in the world.

Nancy 05:48

And I had a sick child, a physically sick child, which changed the whole playing field.

Margaret 05:54

and his seriousness of his illness. And again, you know, the parallels to the powerlessness you felt in his addiction must have been matched on some level of this young child and the powerlessness to get the answers of what was wrong?

Nancy 06:09

It was a very long 25 years of searching, wondering, fearing, it was a lot of nonstop chaos.

Margaret 06:20

When you talk about his early years and his significant illness, do you think that implicated a different way of being in the world? Having watched him suffer and feeling helpless till you got the right answers medically?

Nancy 06:34

Do I think it was a different way that I was in the world?

Margaret: Yeah, with him?

Nancy: I can’t imagine that it didn’t play quite a bit for me. He suffered a lot. Pancreatitis is pretty painful. And took a long time. And then I watched him struggling socially, because he felt really different. And you would never know it. Margaret, he was always the tallest, the strongest, the most verbal, the most physically active, but he had a shield of armor that was miles thick. And underneath that was a very wounded soul. And I think I added to his armor, I wanted to shield him and protect him from hurt, anymore hurt.

Margaret 07:24

Who wouldn’t? What mother wouldn’t?

Nancy 07:28

I don’t know. But I’ll never know. And I wonder what I have been different. I think to say no, would be senseless. I’d have to have, I mean, every experience impacts, impacted me somewhere somehow.

Margaret 07:44

if it were me trying to put myself in your shoes, I can’t imagine it wouldn’t have made me more vigilant.

Nancy 07:50

I was gonna say watchful.

Margaret 07:52

Yeah, well, there you go. Protective.

Nancy: Yeah.

Margaret: Never wanting to see him suffer like that again,

Nancy: Yeah.

Margaret: which would be really good fodder for the disease to work on you with because it would make it really easy for the disease to continue to take him. Because pain was nothing you ever wanted him to feel. I think as a parent, that’s true of all of us, but magnified because of what he went through as a baby and a youngster.

Nancy 08:19

I think that’s 100% Correct. I think my overprotectiveness, my vigilance was compounded by that and was probably 1000 times stronger than it might have been had we not had that experience together. It was hard to say no.

Margaret 08:35

And it is for someone who hasn’t been through that. Right. So it’s 10 times more, I’m sure when you’ve been through that, because it was nobody’s fault. That illness either. There was the sense of guilt that he had to experience it I’m, I’m guessing?

Nancy 08:52

Yes, a lot of guilt, a lot of wondering, Did I do something? Did I do something. And I never felt better than I felt when I was pregnant. It was the best time of my life. I’d loved it. And, you know, Lucas was seven, four and was 22,21 21 and a half inches. He was a big baby. We were happy and suddenly life turned quickly.

Margaret 09:17

Do you think it was your fault? Like, you know, you asked yourself, did I do something wrong? Did I cause this?

Nancy 09:23

I think the thing that helps me with that is believing that we were supposed to live this life together the way that it unraveled.

Margaret: From the moment he came

Nancy: From the moment he came, it was exactly what we both asked for somewhere together on a spiritual level. And that suits me.

Margaret: Good.

Nancy: Because otherwise, you know, it’s easy to take that deep dive into wanting to turn over every, every corner every and there are no answers to be found in that anyway, I don’t know. And if it drank, ate anything bad. I mean, I was just cleaning this, you know,

Margaret 10:07

Like you say it’s a hole, we could go down, and never come out of.

Nancy 10:11

That rabbit hole, can go pretty deep.

Bumper: 10:14

This podcast is made possible by listeners like you. Can you relate to what you’re hearing? Never miss a show by hitting the subscribe button. Now back to the show.

Margaret 10:26

I do remember in the book, many things stand out, but one that does in this vein. Was when you sought answers from your pediatrician after Lucas passed? Can you talk about that? Are you willing to share about that?

Nancy 10:42

Yes, I had met Dr. Gabor Maté, who I love and cherish and, and learned a lot about trauma and early medical trauma, and the impact of that on addiction. And it spurred my thinking, a. how much of an impact did this has medical trauma have on his addiction? And how much did his exposure to opioids have and his proclivity towards addiction?

So, I picked up the phone and I called Dr. Steven Dalton, who I adored who saved Lucas’ life and was a remarkable guy. He called me back in really minutes, said, I don’t know if you remember me, or Lucas, I told him and he said, you know, Nancy, I’m a scientist, I’m a surgeon. I’ve operated on 1000s and 1000s of children. I don’t know. I think he told me there was a couple of other youngsters that he operated on that he learned, also struggled with addiction. But he encouraged me to do a study, which I did not do. On early childhood medical intervention and addiction. But I do believe that there’s definitely a correlation. And he did not know, of course, what the intensity of all those opioids that Lucas had, did to his system, to his neurological system, to his brain. You know, I do believe that Lucas’ brain the first time, and he will have said that about pot. I don’t know about opioids. But the first time he took the toke, he was home and his early brain, every time he was in pain, it was in the hospital, got something that made him feel better. So, for me the correlation between physical pain, psychological, emotional pain, they were all the same thing wrapped into one. He knew where to go to get rid of his discomfort. And I think, you know, this surgeon’s response was appropriate, and I think he was also curious.

Margaret 12:44

Oh, I have no doubt. And I hope that somebody will is doing a study along those lines, I

think that would be very helpful information. One of the lines that an old supervisor used to say was who has an audition for the part of addiction? The only people we know are those who’ve never tried a mood-altering substance from nicotine to any of them. And yet, in some people, a switch is flipped.

Nancy: Yeah.

Margaret: And in Lucas’s position. That appears to have been the case that he had that switch flip, whether it was from childhood, or whether he never had that happen, but he still had the disease and started as an adolescent.

Nancy: Exactly. I’ll never know.

Margaret: No, and whereas other people who don’t have this disease, that does not happen.

Nancy 13:24

That’s what’s so astounding to me.

Margaret: Me too.

Nancy: And I think, as one therapist in New York said to me, who Lucas actually adored him, the only one, he really related to. Said, some people don’t have the off switch, Nancy. And Lucas did not have the off switch. It malfunctioned. And he didn’t,

Margaret: Right.

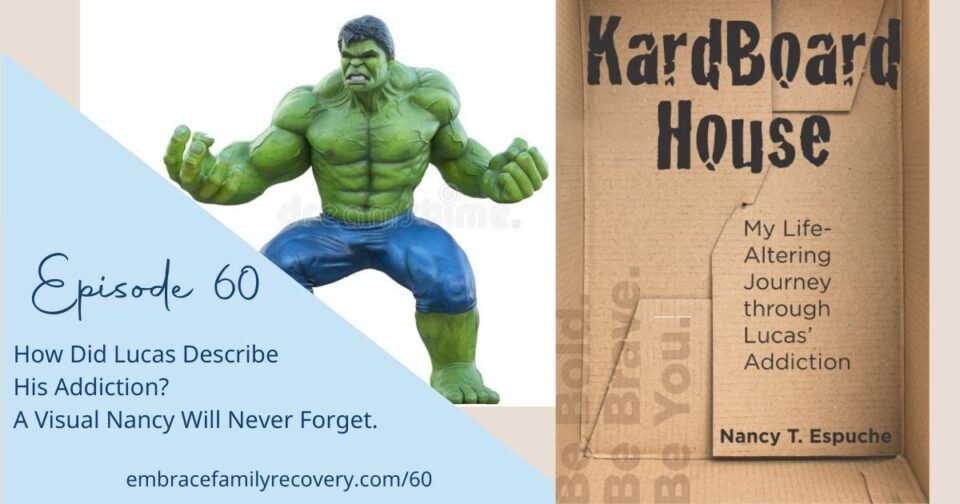

Nancy: It was too big a monster. It took so much strength for him to even want to open up that peep hole and take a look. When he was about 17, we were in a therapy session together. And the therapist said to him , you’re either going to become a full blown addict, die of an overdose, or save your life. And I admired him for saying that. He’d say, can you in a quick picture, tell me what it feels like to be you? And Lucas said, I feel like the Hulk lives inside of me.

Margaret 14:25

At 17?

Nancy: Yeah.

Margaret: So, your interpretation is that the Hulk was the disease.

Nancy 14:31

It was a monster. It was a big, overwhelming, big green thing that could overtake anything, anybody. That Lucas was under this monstrous power, I never forgot it.

Margaret 14:45

And it’s a very powerful visual of the disease that lives within a person uses their voice to manipulate them and is more powerful than they are.

Nancy: Yes.

Margaret: And it’s ironic because the Hulk is a very standard to normal looking guy before that happens, but it’s his same voice in both bodies. It’s kind of powerful I, wow. I like visual representation to help people separate out the disease from the person. Because that is one of the biggest parts of the healing process for both people with the disease and people around the person with the disease. And it’s so baffling to do.

Nancy 15:25

I can give you a visual, I recently called my therapist, I was having a hard time about all of this. And I don’t know if they had it here. But where I grew up in New York, if you went to when you went to gym as a kid, you would climb the ropes.

Margaret: Oh, yes, I had it.

Nancy: So, and we had these gym clothes on that were, you know, short for them. I said, I feel like I’m climbing the rope. And then I lose my grip. And I get rope burn sliding down. And then I go to climb the rope again. And I lose my grip. And now the rope burn is even deeper. And I said, how do I stop burning myself?

Margaret 16:07

What answer have you come to?

Nancy 16:09

I don’t remember his words, I know that it was a very overwhelming moment for me in that room. Because I you know, you can Band-Aid only so much. You have to really look at your wound, clean it out as best you can.

Margaret: Which is painful!

Nancy: Which is very painful. You know, even Lucas is gone now. It was five years in December. The first year I was, I don’t even know where it was. When the second year came, I went how could this be worse than the first year. And it was. the second year was awful, as reality really set in. And I think, you know, metaphorically, you know, as you try to clean out that wound. sometimes you have to go deeper because there’s more scrapple or rope burn, rope pieces in there that you need to get out. And I think for me, it’s like, I know, there’s more in there that I gotta clean out. But yuck.

Margaret 17:09

So let it come to the surface when I can’t ignore it. And then I’ll do it?

Nancy 17:14

To a degree, but not so much because I’m a looker. And I’m, I don’t want to run it and I keep hearing Lucas go short turn mom. And I won’t really embrace that more fully. I don’t think ever fully fully, but more fully, until I allow myself to really feel the depth of my grief.

Margaret 17:39

What does your turn look like on a regular basis for you? What have you created with in the reality of this terrible grief for yourself?

Nancy 17:49

I want to find joy. I want not to even be around a room of people smiling and laughing and me participating. But still feeling like something is cut from my neck, that I can’t really forget my anguish. I want to be more willing to participate in life’s events. Being out well, you know, the pandemic sort of changed a lot of that anyway,

Margaret: Of course,

Nancy: but maybe, you know, moving more towards that this late spring, summer. I haven’t laughed in a long time.

Margaret 18:22

So, a question I would ask about that. Moving towards joy is one of the strategies I use with my family members in just living in the disease and the recovery process. That this disease will suck the joy out of every room. Doesn’t even touch what I know you’re speaking to around grief and the joy of being taken by the loss of your son. I that is not the same. Were you experiencing joy before he passed?

Nancy: No.

Margaret: Because he was so on the throws. I struggled a lot. And I answered that I know very quickly.

Nancy 19:00

There were times, episodes, moments, blocks of time, but I was always watching. When’s it coming back? What’s, what’s happening, what’s happening, what’s happening? And because we were so close, I was always on the other side, and I knew. You know, all Lucas had to do was say hi, and I knew exactly where he was. I really struggled separating my life and Lucas’ life. I think I knew what was coming somewhere on a semi-conscious level. And I think I was holding myself as best I could together, trying to hold him together. So, my days were a struggle,

Margaret 19:43

And I hear that a lot from families. That is not unique to you. And you know that being in the rooms of NarAnon, that it feels like joy is sucked out of our life. The disease hijacks it, and one of the parts of the surrender of a family member’s recovery is bringing joy back. Not letting the disease take it from them. Little glimmers by little glimmers. I would imagine that as you’ve lost Lucas, that would have felt incomprehensible for a long period of time.

Nancy 20:16

It did. And you know, I see other people in my shoes, some can’t get out of bed, some are traveling and going on with their lives and laughing. It’s, you know, it’s just my own private experience.

Margaret 20:32

And speaks to just as in the disease of addiction, there is a commonality we share. We each have our own nuances in our own story. The same is true of grief. There are some commonalities, but everybody’s nuances are different and should not be judged.

Nancy: Yes.

Outro: Nancy’s grief is so palatable, as the love you hear in her voice when she shares about her son. Many grieving people have shared with me how much they want to speak about their loved one who’s gone. Listening to Nancy Espuche reminds me that I want to be a good friend to the people I love who are grieving. And so, I’m going to remember to ask questions, hear stories, and share stories.

I want to thank my guest for their courage and vulnerability and sharing parts of their story.

Please find resources on my website, embracefamilyrecovery.com

This is Margaret Swift Thompson.

Until next time, please take care of you.