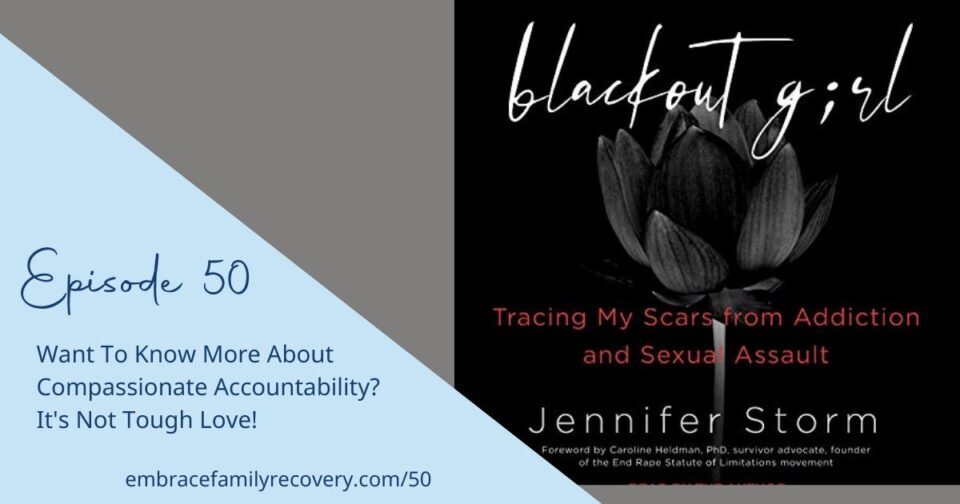

What an honor it is to have Jennifer Storm, the author of Blackout Girl as a guest today!

Jennifer shares her belief that hearing another’s story helps us connect to our story and lessens our sense of isolation. When I say I read this book from a place of genuine curiosity about another woman’s recovery journey, that would be true. I had no idea how impacted I would be by Jennifer’s eloquence and fearlessness to write her truth on paper for the world to read. I am in awe of Jennifer’s courage, tenacity, and spirit of service.

Jennifer taught me a new term, compassionate accountability, and I love this term and its meaning.

Jennifer Storm is the author of six critically acclaimed books on addiction, recovery, and victimization. Awakening Blackout Girl: A Survivors Guide for Healing from Addiction and Sexual Trauma, Blackout Girl: Tracing my Scars from Addiction and Sexual Assault, Second Edition, Echoes of Penn State: Facing Sexual Trauma, Picking Up the Pieces Without Picking Up: A Guidebook Through Victimization for People in Recovery, Leave the Light On: A Memoir of Recovery and Self-Discovery and Blackout Girl: Growing Up and Drying Out in America.

Below is a link to Jennifer’s extensive page for help and resources.

https://jenniferstorm.com/get-help/

See full transcript below.

00:01

You’re listening to the Embrace Family Recovery Podcast, a place for real conversations with people who love someone with the disease of addiction. Now, here is your host, Margaret Swift Thompson.

Margaret 00:23

Welcome back, I have the privilege of meeting amazing human beings on a regular basis in my practice on my podcast, and today is no different. I get the honor of introducing you to Jennifer Storm, the author of Blackout Girl. When I say I read this book, from a place of genuine curiosity about another woman’s journey of recovery, that would be true. Add to that Jennifer’s eloquence and her fearlessness to write her truth on paper for the world to read. Please meet Jennifer Storm.

01:05

The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast.

Margaret 01:17

I am both humbled and honored to meet you, Jennifer. I had heard of your book and had not looked at it. And then I picked it up and read it after I got the privilege of being in a workshop with you, where you were working with people to write their own story, whether for publishing or not to use the power of writing for healing, if I say, right, is that how you would interpret it?

Jennifer: Absolutely.

Margaret: And I have toyed with writing my story for gosh, people have told me and over and over and I should and I’ve never been able to put pen to paper and in your workshop I was able to put pen to paper write things and feel things I hadn’t in a long time it was when it was what an hour we spent together.

Jennifer 02:00

Yeah. That’s amazing. That makes me so excited!

Margaret 02:03

So like I feel a bit like a girl fan. Like I’m like, oh, I’m with Jennifer. (laughter)So, we’ll try and get past that and have an articulate conversation. (laughter) But I want to first welcome you and say that your courage to put your story on paper blew my mind. And I wonder for the audience, to hear from you rather than me. What led you to write your story? What, like a glimmer of some of what the content is. Because there are people on this podcast who won’t have heard of you. And I want them to get to know you and see the benefit of maybe looking into reading your book, or books. We’ll talk about that after.

Jennifer 02:46

Thank you. Yeah, writing, for me was always a form of expression, even as a child. So, I started writing as early as I could write, and creatively. So, I have like my first book, I think it was from first grade that I wrote, and then subsequent pieces of writing, I still have some of that. So it was always a creative outlet for me. And you know, I lost my best friend when she was 15, she had committed suicide she had taken her life, made the decision to end her life. And I was also raped at 12. So, I had these like two incredibly profound things that had happened and completely altered my life. When I was raped, I really had a hard time articulating that experience, and a lot of it has to do with neuroscience and trauma and the way we as children kind of, you know, experienced trauma and how we can access those memories in our brain, right? So, I couldn’t really articulate what I was going through. So instead, I just would stay up all night long, which I now when I entered into a method of healing, I realized I was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. I didn’t know that I was 12 years old, my parents didn’t know that none of us knew that. We didn’t really have those commonly known labels as we do today. And so, I would sit up all night long, and I would write morbid poetry, mainly about death, you know, suicidal ideation, that kind of stuff, but just really dark. But good poetry, right. And so, I found that, just the ability to write helps. And then when my best friend made the decision to enter life, that grief was so, so intense. And so, I wrote a story for my creative writing class about that. And so, writing just was an outlet for me.

And while I was going through kind of my formative years, and I turn to substances to deal with the trauma that I was experiencing, you know, I was quelling those formative years with substances, but still trying to survive them and the way I survived them was by getting high and getting drunk. And so writing every now and then would pop up. But I kind of abandoned it when I found drugs and alcohol, to be very honest, it was

Margaret: Sure,

Jennifer: really instrumental early on, and then I totally let it go. And probably in my 20s, I started journaling again. And although I will say this, I had like a calendar journal, where I track things, but they weren’t like feelings and emotions. But I do have the journal that I started using in my 20s, in my early 20s. And what it started to happen was, I started getting flashbacks, and I started having reminders and trauma triggers from all this stuff. And there was a whole lot more than I won’t get into, you know, people, if they read the book, though, they’ll discover everything else. And so, I started to write, and I started to journal. And then when I got sober, when I went to rehab, I realized that I didn’t feel comfortable yet, speaking my trauma, and openly sharing about a lot, I had a lot of trust issues, just very common when people are coming into early recovery. So, I would entrust all that information into my journal,

Margaret: Right.

Jennifer: So that like, it’s just a lifetime of writing and processing. And but it wasn’t until I got clean and sober in 1997. And it wasn’t until probably 2005/6 that I started to think, oh, maybe I maybe I could actually publish some of these things.

And so I had so much of my story written because I really took to heart not only the 12 steps that I had been working in at the time, but the trauma work that I had been doing in therapy and writing and unpacking all those events and experiences just kind of led to this massive file that I had on my computer that eventually turned into Blackout Girl.

And I was also an avid reader at the time. And you know, the early 2000s memoir, as a genre was just bursting onto the scenes. And there were recovery books, right, wrong, or indifferent that started to really garner a lot of attention. Obviously, the one that I’m not even going to name because I don’t think it was ethical because it was fiction and not a memoir. But there was a lot of attention around recovery memoirs.

So of course, I’m reading all of these, right, because I you know, I love to read to and I think the best way for us to learn and connect with experiences is by hearing another person’s story that is in some way similar to ours, or that helps to bring into focus, maybe an aspect of our story we didn’t even know about. So, as I was doing that, I was like I don’t I’m not really finding my story. Like I’m not really connecting deeply with some of these narratives. And so, I just kept going back to my own file, which then turned into a manuscript which I then you know, like I said, turned into my first memoir, which is Blackout Girl. And it was published in 2008 by Hazelden.

Margaret 07:53

My audience is mainly family members of people who have addictions of some kind. Though anybody I think can benefit, like you say, hearing stories to connect. We know, you and I that trauma and addiction are very closely intertwined. And you speak to in your book, especially towards the end, which I found very powerful, because you gave some really good comprehensive, what I would call nuggets of information to give people a different window to look in for treatment and healing from both trauma and then addiction. And I wonder, for families who may be listening, is there anything that you can imagine could have been different for your story? Through family, knowing more, understanding more approaches, you know, in hindsight, 2020, right, it is what it is.

Jennifer 08:47

(laughter) Yeah. And it’s interesting, because I’m a parent now, right? So, I have a six-year-old son, and I have a 23 year old daughter who came to me as a foster child at age 16. Just incredible traumatic experiences in her in her life. And then she has a little one. So, I’m like now surrounded by little people, and I have this awesome responsibility of parenting. And I can tell you that I’m parenting in such a different way my children than I was parented, and I don’t fault my parents. My parents had the resources that they had. They were very limited. Both my parents came from their own traumatic backgrounds that were untreated, undiscussed, unacknowledged, and they both came from families that were just riddled with substance use disorder, right.

So, they, when my initial traumatic experience happened, they didn’t know how to respond to me like they didn’t they had no idea what to do with me. And quite frankly, the very presence of my trauma brought up their own trauma, which of course, was something they didn’t want to look at. And they did everything wrong. But they didn’t know better. They have no idea. And really, if you look back, I mean, I was raped in 1987. So, if we look back at the way, culturally and societally we looked at those things, we didn’t.

Margaret: We didn’t.

Jennifer: We didn’t talk about sexual assault. We didn’t talk about family violence. These were not conversations being had at all, maybe a very small research pockets across the country, you know, at universities, and in therapy programs, but they weren’t the everyday conversations. Even in our media. We were only sort of starting to see I mean, gosh, I remember going and seeing, Oh, gosh, what was that movie with? Like, my brain is blanking. It was a horrible rape scene on a pool table. Oh, gosh, what was her name?

Margaret: Jodie Foster,

Jennifer: Jodie Foster. Yes, The Accused. It was called The Accused, right.

Margaret: I remember

Jennifer: Oh, God. I remember as a family. We went to see that movie.

Margaret: Oh, no.

Jennifer: Right after I had been assaulted. And I started to hyperventilate in the movie. I remember, I don’t think I even put this in the book.

Margaret: No.

Jennifer: but I had a horrific experience traumatic re, you know, reenactment of my own situation. And like my parents said, they were like, she’s just being dramatic. Like, what’s wrong with her? Like, it’s just a movie. So, they just had no framework of understanding of trauma, the aftermath of trauma. And so had they had like, a grain of understanding, a fraction of awareness. Had someone just looked to me and said, Are you okay?

Margaret: Yeah.

Jennifer: How can I support you? If somebody were to just acknowledge the harm that was done to me, hugged me, embrace me, supported me, I got stonewalled, and again, they didn’t know any better. They just didn’t. My dad took me to a therapist, but it was like this old guy, I did put this is a book that like, was very traditional therapy. And it just didn’t feel safe. It was a male like,

Margaret: Right,

Jennifer: you know, so that was the only attempt and I wasn’t open. Because it was just not the right modality.

12:01

Bumper: This podcast is made possible by listeners like you. Can you relate to what you’re hearing? Never miss a show by hitting the subscribe button. Now back to the show.

Margaret 12:13

So powerful words that I coach, parents, partners around just substance use disorder and other addictions to, how can I be supportive? Right, not taking on responsibility, but stepping into a willingness to be engaged? Do you think, from what you can share, your parents couldn’t get any closer because of their own unresolved trauma?

Jennifer 12:40

Oh, my gosh yeah. I think I was like, like a flame to them, right. And it forced them to look at their own stuff, which they didn’t want to look at, didn’t want to feel or talk about or discuss. My mother was a daily valium addict. That was from her own trauma. My dad was more I mean, they both smoked marijuana and they drank like they didn’t drink alcoholically, but they drank. And my dad just worked, and worked, and worked, and worked. So, my dad had childhood trauma, and he had PTSD from Vietnam. He was first infantry, Vietnam, right. So, he saw the worst of the worst of it, got the worst of the worst of agent orange, all that stuff. So yeah, I think that I was like a flame. And they just they couldn’t acknowledge what had happened to me.

Margaret 13:21

And I think that’s really telling. And I think that, again, is really great information, awareness for families out there, that some of their resistance may not be anything to do with the person, they identify having the issues, but may totally be their unresolved work for themselves. And to have a willingness to do their own recovery, work, therapy, work, whatever it may be for them, so as to be able to be present with their child, their partner, whomever it is in their life.

Jennifer 13:48

Oh, yeah. And listen, it’s probably, well, it’s really hard to go through traumatic experiences and go through addiction. It’s also equally as hard to watch somebody you love go through all that. Because the powerlessness is so thick. And you can do all the right things, say all the right things, resource all the right places, and still wind up with an individual who’s just not gonna, not gonna get It, or not gonna want to engage. And so there there has to be a willingness to know that you can’t save that person. You can’t fix people. You can love them, you can resource them. And then you can also set up healthy boundaries for yourself so that you’re not getting hurt, and you’re not getting kind of pulled in to the toxicity and the trauma and the chaos that often surrounds active addiction. Those are really hard things.

Margaret 14:40

Absolutely. And I would like to go a little further on that because I think you said very clearly, I don’t hold my parents responsible. It’s not their fault. And parents really struggle with boundaries and caring for themself and protecting themselves from the toxicity, the chaos, the disease. I feel it’s vital to do that. To navigate this journey. It’s vital. So, if you had a parent who had a child who’d been through similar to you? Do you have advice for them?

Jennifer 15:20

Yeah, I mean, I think and this is probably a little antithetical to what should be done. But the one thing my parents that my dad, so when I say parents, I grew up with my biological mother and my, my biological father. They divorced when I was 15. And my mom kind of, she kind of pieced out.

So, when I talk about my parents, my parents and became my dad and my stepmother. What my dad always did, right? Was he always unconditionally loved me. I never went to bed without hearing the words, I love you. And that is something that really had a profound impact on me.

And as I started to grow older, and then he married my stepmother, the one thing they never did, is they never rejected me. And they never judged me. In that, they probably, I mean, they enabled a lot of behavior that they probably shouldn’t have. But I will say like, there was something incredibly beautiful about that unconditional love. It allowed me to bring to them my crap, right, when I was ready.

And so, it enabled them to be a safe place for me. Like I remember, when I was 19, and I got pregnant, had they not been that unconditional, loving unjudgmental place for me, I probably would have never even told them. And that would have just been this other traumatic thing that I went through alone. And actually, I ended up telling them and they helped me through all of that.

So, you know, I think they probably could have been better at drawing boundaries. And I see them with my both my brothers had substance use disorders as well. But the unconditional love and the support was huge for me. And it’s something I do for my daughter now.

Now, I set up boundaries. And the one thing my parents didn’t allow was disrespect, right? Like if I was living in their home, I respected their home. And if I didn’t, that I would that I would have gotten put out, right. So, you think you know, unconditional love, support with boundaries, like you’ve got to hold people compassionately accountable. I don’t believe in tough love. I don’t think it gets anyone anywhere. But I do think you have, you can hold people compassionately accountable. And I do that with my daughter now, my daughter is 23. And she’s not dove into her own trauma. And so, there’s a lot of, a lot of stuff around that. And I try to love her unconditionally. I hold her compassionately accountable by having really hard conversations with her. And I call her on her stuff, right? Like I don’t let her treat my home disrespectfully. There are people coming in and out of my house shouldn’t be here. And there was a point in her life where she was not doing that. And I packed up her things and I helped her move out. They said you gotta go like, I love you. And you’re welcome here but if you can’t abide by my rules you got to go. And that was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. But she’ll probably tell you it was you know, one of the best things that happened. Now she is back in my home and living here respectfully.

Margaret 18:26

And I hear that a lot from families that though that was the most painful boundary to set. I hear from both sides’ majority of the time and it was what helped me get honest about needing to do some things different. So interesting, you don’t use the word tough love which I don’t either however, someone out there listening my thing well, you know, packing up her stuff and saying it’s time to go could be considered tough love.

Jennifer 18:52

Sure! I call it compassionate accountability. That’s just my term.(laughter)

Margaret 18:55

And I like your term a lot. Because I think it is I don’t think it has to be either or and I think people get stuck in that how do I love unconditionally and hold boundaries that feel like abandonment?

Jennifer 19:05

Yeah. And so I guess you do it in a way that is compassionate, right? I wasn’t abandoning her, and I was telling her every step of the way you are more than welcome to stay here. You just have to be willing to abide by the rules. And she wouldn’t

Margaret: right

Jennifer: then and when she left. I was still checking in with her What do you need? Are you okay? You’re more than welcome to come back here if you can abide by these rules and she, you know made the choice for probably about a year and a half to not, right and so she sofa served and did what she needed to do. But I was still there for her she knew I was still a phone call away.

Margaret: Right?

Jennifer: Tough love, I feel like is when people just turn their backs on individuals that they feel like they can’t help. And you can still help that person while maintaining your boundaries and and being safe. It just looks a little bit you know looks a little bit different. I wasn’t gonna throw her out and then tell her she was never welcome back and don’t don’t ever, you know, call me or, you know, things like that.

Margaret 20:06

When I think, you know, maybe nuances and language. I don’t think those are boundaries.

Jennifer: Yeah.

Margaret: Those are ultimatums and threats that I hope I’ll never have to act on. But maybe they’ll snap you to those don’t work.

Jennifer: Yeah.

Margaret: I mean, I haven’t met an addict, including my own story. Who wouldn’t test a boundary if I could?

Jennifer 20:27

Oh, my God. Yeah. Yeah, I loved boundaries. They were I was like a horse in a, you know, hopping ring. Like, let me see how far I can push it and then jump over? Very much so, yeah.

Margaret 20:38

I think our disease thrives on that stuff. And so the compassionate love the showing up the maintaining an open door through a phone call through checking in, through showing love for the person and separating the person from their disease as much as possible.

Jennifer 20:54

Yeah. Because then you become so like, when I do trainings, and I keynote and speak on my book, people will ask that question like, What could have helped what, would have helped and all we can do is be seed planters? You know, we drop seeds of love, we drop seeds of resource, seeds of education, seeds of awareness. And at the end of the day, like, what I know to be true is that our brains are amazing. And while we can selectively choose to ignore things, when you learn something, it’s really, really hard to unlearn that thing. And you can’t unlearn right? Because we know that with like, racial inequality and, bias and hatred, you can unlearn those things. And you’ll always have an awareness that you knew that at one point, or that you thought that way, at one point, and then you’ll learn something new. It’s really hard to like forget something someone tells you, especially if it’s like impactful. And it’s really hard to forget how someone makes you feel. So, if you are a person that’s constantly sprinkling support, and sprinkling resources and doing it in a loving and compassionate way. You’re probably going to be the one they call when they need help. They’re not going to call the one that’s calling them a loser and a piece of shit and kick him out of the house. They might but probably gonna call the other one.

Margaret 22:11

When I think to your point, while active in the disease and absolutely reading your book, the level of my words, self-loathing is palatable. So, any chance there could be a loving nugget left touched, even if it doesn’t appear to penetrate.

Jennifer: Yeah,

Margaret: is huge.

Jennifer 22:35

Well, yeah, we hate ourselves enough in our active addiction. We don’t need you to tell us somehow how much of a piece of crap we are. Um quite the opposite would be helpful.

Outro 22:47

As I read this book, The Blackout Girl, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own life and some of the overlaps of our stories. To bare your soul is no easy feat. However, I truly believe with Jennifer’s generosity and desire to be of service, she offers women hope and comfort in not being alone with the story of addiction or sexual trauma and loss. Come back next week when Jennifer will talk more about her story of how it went from journaling for her care for herself to writing it and publishing it for the world. And some concrete examples of how family can come alongside loved ones who have been through trauma and struggle with substance use disorder or other addictions.

I want to thank my guest for their courage and vulnerability and sharing parts of their story.

Please find resources on my website.

embracefamilyrecovery.com

This is Margaret Swift Thompson.

Until next time, please take care of you.