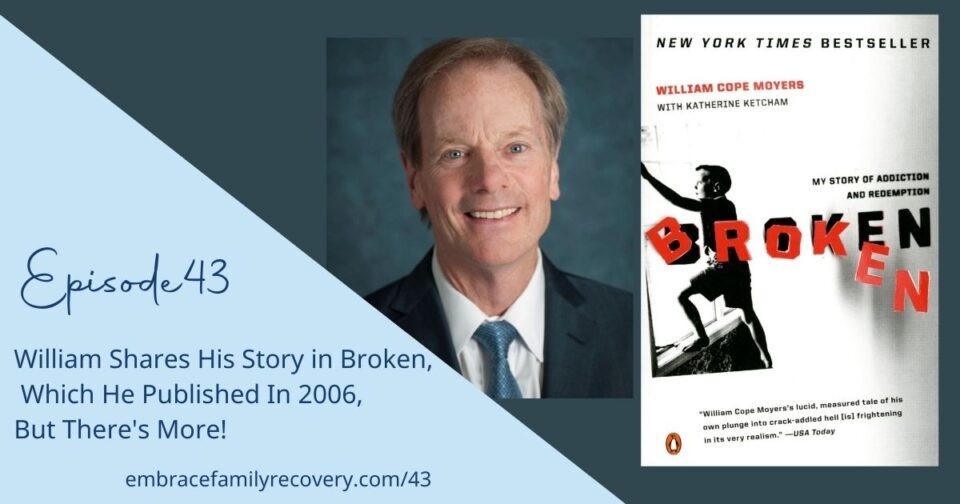

Today I am thrilled to introduce you to William Cope Moyers, a man in long-term recovery who wrote his Memoir, ‘Broken’ in 2006. William was a trailblazer of sorts, willing to write his book and his truth about his journey with his Substance Use Disorder and recovery.

The inclusion of letters from his father, Bill Moyers, introduced a poignant vital perspective – the impact of the family disease of addiction.

As you will hear in this episode, much has happened in William’s life and family since ‘Broken’ was published.

The disease of addiction is complex, baffling, and full of layers of growth and healing if we are willing to buckle up and engage in our recovery.

William is a man who works his recovery, and as he says, he has “been walking that walk imperfectly.”

If listening to William raises a desire for more help for you as a family member, please go to my website

embracefamilyrecovery.com

and complete the ‘Work With Margaret’ page.

We can then have a complimentary discovery call to see if we would be a good fit to work together.

You never have to be alone with this disease again unless you choose to be.

See full transcript below.

00:01

You’re listening to the Embrace Family Recovery Podcast, a place for real conversations with people who love someone with the disease of addiction. Now, here is your host, Margaret Swift Thompson.

Margaret 00:24

Welcome back. Today, I am excited to bring you a person who has publicly shared his story of his substance use disorder for decades now. William Cope Moyers wrote his memoir, Broken in 2006. He has served to put a voice, face, name to substance use disorder and recovery. I have recommended William’s book Broken to many families along this journey of healing. William does a phenomenal job of sharing his journey with substance use disorder. And he offers great insight into the experience of his family surrounding his illness. Please meet William Cope Moyers!

01:14

The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast

Margaret 01:25

The biggest awareness I have of William, your story in this realm is just the power of your book, the book Broken, I’ve referred that to more family members than I can tell you. And I think one of the most powerful parts of your book, other than your authenticity and honesty and sharing your story, was having your parents’ involvement. To be able to hear glimmers of what they were going through that was a pivotal change in what I perceive as the availability of that type of information to the public.

William: Yeah, so yeah.

Margaret: What would you like to share about the journey of writing broken? I mean, you could share about your journey, but I’m really curious about that journey of bringing them into the into the book.

02:07

William: Well, thanks for picking up on that, Margaret, I appreciate the opportunity to be with you on your podcast today. You know, not too many people have asked me about that element to it. And by the way, you know, Broken is 15 or 16 years old is still in print, fourth printing. And that’s all great. But it is a segment of my life. I’ve had 15 or 16 years, since then. And I’ve had the highest of highs and the lowest of lows as a person in recovery. And maybe we can talk about that later. But broken does resonate not just for people who are struggling with or trying to overcome a substance use disorder, but with family members. And a big part of that is because my parents are so formative in my story just like they are in my journey. And I think the reason why they’re formative in that book is because they allowed themselves to be part of it. They gave me “permission”, not only to share our interactions and our experiences, but also really critically to share their letters, particularly my father’s letters. You know, we don’t write letters as a as a species much anymore. And yet letter writing is important to communications, or it was. And my father’s letters, he being a journalist, Bill Moyers, he wrote me lots of letters growing up, and because he’s my dad, and because he matters, I could never dispose of those letters. So, I kept them. And I saved them in a big camp trunk, one of the shipping trunks. And, and so when I wrote Broken, I began to delve into those letters. And I asked him if I could have permission to use them. And he said, yes, with one exception, there’s one letter, he didn’t ask me, one didn’t want me to share, and I respected that. So, the authenticity of my story is also the authenticity of a family struggle with this illness.

Margaret: Right.

William: And as you know, through your own experiences, addiction is a family illness. So, you know, I dedicated my, my book to them, I said to my, to my parents who’ve been with me every step of the way. And they have been, and by the way, my parents are still living. My dad is 87, my mother’s 86. They’ve been married for 67 years.

Margaret: Wow,

William: They’re in declining health, but I still see them and they’re still formative in my life. Even though today, I’m 62, you know, so, they’re still walking with me one step at a time.

Margaret 04:37

And one of the things that that came across in the evolution of your book was their journey to understanding it was a family disease, right? Which is a journey every family goes through. It’s very often get them the good care which they’re invested in doing. And then there will be okay. But they also embraced their own education and support through family programs through avenues like that, is that correct?

05:03

William: Yes. I think they were reluctant to embrace that, not because they didn’t want to, but because it didn’t understand that they needed to. Yeah, I mean, I think they had a fundamental understanding. I mean, they’re learned people. They had a fundamental understanding of their son’s addiction in not only his life, i.e., me, but their own lives. I mean, addiction takes a terrible toll on everybody that loves the attic of the alcoholic, I don’t think they quite grasped that they needed to be active participants in the process, not so much for my benefit, although it benefited me but for their benefit. Because, as we know, particularly with the opioid epidemic, where unprecedented numbers of people are dying from this illness. The loved one, whether it’s a parent, a grandparent, a spouse, a sibling, significant other, that person needs to recover, even when the addict to the alcoholic doesn’t recover or worse dies.

And I think my parents sort of came to that slowly through an evolution which is endemic, I think with lots of family members, my parents came to the Family Program at Hazelden in the fall of 89. When I was treated, there 32 years ago right now, and that began this journey for them. But Margaret, I gotta tell you, that was not the sort of light bulb moment for them. That moment came not until 1994, when after multiple treatments and several years of abstinence, so I was not recovering in the context of how I recovered today. But I was not using, I relapsed, I had a recurrence of my use, and that jarred my parents, because by that time, I was a father to two little baby boys, and married to a woman who was in recovery herself. And yet, despite all of those reasons for me to you know, stay recovered, I didn’t. And it shook them to their core. Because while they had a fundamental understanding of the illness, they did not really yet grasp that recovery has to endure no matter what. And I had sort of thrown it away, if you will, thrown away my relationship with my children, the relationship with my sober wife, the relationship with my own recovery, my relationship with my job at CNN. I threw all that away to go get high again in a crack house. And that shook them, shook them to the core. And it was through that family experience at a treatment center in Atlanta called Richview. That they sort of got the rest of the experience.

Margaret 07:38

That’s a very valuable piece of information to share. I think that, you know, there’s often the theory of one and done, versus relapse is a symptom of this disease that not everyone experiences. But if we don’t work our program, it’s a very real possibility. And so, for families, I always parallel it to their relapse process.

William: Yes.

Margaret: Right. So, your parents had an exposure, gain some valuable insight, I’m sure from their first experience in a family program, and then you stabilized in your abstinence to a point that they were probably like, (big breath), which every family does. And if we don’t maintain our vigilance to our family recovery, when that relapse happens, that spiral for everybody?

08:25

William: Yes, yes. And, and then for them, there was one more piece of it. And we were talking off microphone about people that we know from the past, and how it was I ultimately got to Hazelden. But I had occurrence of my use in the fall of 94, October 12 of 94. It was when I came out of what I hope is my last crack house. Last time I had a drink, October 94. And that, of course that relapse experience and their family experience were jarring. But then there was this last piece, which is that shortly thereafter, my mother was recruited to be on the board of Hazelden, and at that time, I didn’t work for Hazelden, I was still in Atlanta, but she got recruited to work to come to the board. And she became a member of the Board of Trustees in about 1994/95. And it was while she was a trustee. Again, I wasn’t working at Hazelden yet, that’s another story. But she came to Center City, Minnesota to hear a lecture by at that time, the head of the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Steven Hyman, and it was Dr. Hyman who spoke about the nature of addiction being a brain disease. In other words, having its origins in the brain, though, as we know, it’s a lot of other things too. And it was that experience, that lecture that my mother heard that opened her eyes to how it was that I relapsed. That craving brain again, didn’t excuse the things I did, helped to explain them. And that was another one of those eye-opening moments for Judith Moyers and then she went back to the New York and told her husband, Bill Moyers, my dad, the same thing. And out of that experience, came a five-part series on PBS called ‘Moyers on Addiction, Close to Home’. And, um, and that sort of opened the eyes of the nation to the fact that addiction is an illness with a brain component. And it is a family disease. There have been lots of other people who’ve been talking about that. But I think it was my parents experience as parents, and also as the journalists, that they’ve been for a long time, that they put those two things together. And they had that sort of that aha moment.

Margaret: Yes,

William: It was not only important for them personally in their own recoveries, but important for the nation as we sort of came to terms with addiction as a relapsing, chronic disease that has its origins in the brain.

Margaret 10:45

Service is obviously a vital part of your recovery. Apparently, theirs. Because just speaking to that, that they were willing to do that work, to share that work to help more people who would never get exposed to it understand this disease.

If you are listening to this podcast, finding it helpful, but long for more support.

Please go to my website,

embracefamilyrecovery.com

and sign up to receive your complimentary copy of

Healthy Strategies For Family Members to Cope and Even Thrive Through Addiction.

11:17

Bumper: This podcast is made possible by listeners like you. Can you relate to what you’re hearing? Never miss a show by hitting the subscribe button. Now back to the show.

Margaret 11:28

I’m curious, William to go back to what you said. When you had your last return to use, you were married, and with someone who’s in recovery, and two children, and you shared you were abstinent, but don’t work, the recovery you work now, and you are now abstinent. How long? How long have you been in recovery? Since then?

11:51

William: Well, I’ve been committed to my recovery. Margaret, Margaret says the morning of October the 12th of 1994 When I came out of that crack house, so you know, I’ve been I’ve been walking that walk imperfectly, but walking that walk since that morning. As many things that are important to me as they are, nothing’s more important than my continued recovery. And so, I’ve been in recovery, I mean, in committed recovery since that date, October 12, 94.

Margaret 12:17

And when you look at pre that date, and your abstinence and the work you did in recovery versus now. Because a lot of people perceive recovery in the beginning is so intense and so committed, and then you can kind of back off because you’ve got this. Which as a recovering person, you and I know that’s not true. Explain if you would to the audience, what is different about your recovery journey, and what you use to maintain your recovery today that was different than pre relapse?

12:47

William: Yeah, I used to see, this is a great question. I used to see my recovery as part of me. I didn’t see it as all of me. You know, I was treated at Hazelden in 89, I was treated again at Hazelden in 91. I had that period of abstinence between 91 and 94. I thought I sort of put my illness behind me. I wasn’t denying anything about the past and I had the fundamental tools that Hazelden as we were then called now Hazelden Betty Ford but Hazelden. They’ve given me the tools of recovery, which not only was about abstinence, but it’s all about those components of the mind and the body and the spirit and I, I knew them and for a while there in those early 90s I sort of “worked them”. But I just saw my recovery as part of me. I didn’t see it as all of me. And so, I you know, I remember my counselor at Hazelden, George Weller said to me that the only way we coast is downhill. And you know, I was coasting. But I wasn’t coasting uphill, I wasn’t coasting up in my recovery, I was coasting down into something tricky. And that happened in 94. So, when I came out of that crack house in 94, went back to treatment and stop trying to do things my way. I knew that I needed to put my recovery first, that doesn’t mean that I don’t think about other things first, or in the beginning of the day or during the course of the day. But I began to embrace my identity as somebody who needed to be in recovery.

I define recovery differently today than I did in the old days. And we can come back to that. But to the point about service work. I have found my vocation, I got really lucky. Maybe I was blessed. I don’t know, I got hired by Hazelden in 1996. And by Jane Nakken, who was an executive in the organization, and she took my resume, plucked my resume out of 100, a stack of 100 and I got the job and I wasn’t probably the most qualified for it, I got the job. From that time on Margaret, I began to realize the importance of my recovery in the context of not just my own life, but in in the work that I do. That wasn’t it, that work wasn’t going to protect me from the disease being cunning, baffling, powerful, and patient, but it was going to give me a purpose. And I think that purpose, that vocation, that voice is all about me, you know, standing up and speaking out and exposing myself as a person that I am, and thus helping other people. And so, I think helping other people has helped me more than anything that I could do, as it relates to my own recovery. More than going to recovery meetings, more than getting on my knees, more than working my recovery program. It’s that responsibility and that commitment to other people, even in this dialogue that you and I are having, knowing that there’s somebody out there that’s going to hear this and want help. It is that commitment to other people that I think helps me more than anything.

Margaret 15:55

Well said, I think that the piece that comes to mind for me, and where I’d love to go a little bit with you is you’ve had this disease on every side of your life, not only live it, as a person in long term recovery, thanks to your recovery work, and the higher power that you believe in. But you’ve also experienced it in people’s lives that you tremendously love. I hear from every relationship point of view, this was the worst or that was the worst, or this was the most challenging. And I’d love you to share with the audience from your experience. Is there one relationship that was more difficult to navigate when it comes to being a loved one of someone with this disease than another?

16:47

William: Oh, that’s a hard question. In Broken, the mother of my now three children, Henry and Thomas were little when we lived in Atlanta, and I had my recurrence of use. Tom, Henry was 20 months old Thomas was five or six months old. We subsequently, Alison and I had moved back to Minnesota and our daughter Nancy was born in 97. So, the mother of our three children, Allison, um, you know, she was formative in the book, she’s a hero in some ways, because she stuck by me.

But Alison will be the first to tell you. And I think she’s a fan of this podcast. So, I want to be respectful here, but also authentic and honest. Um, she and I well I make a reference to it towards the end of Broken She struggles mightily with mental health issues she has for a long, long time. And what most people don’t know, if you just read Broken is that our relationship didn’t survive. It didn’t survive my humaneness. And it didn’t survive her struggles with mental health, which she’s open about, and we’ve talked about it. Because we’re friends today, we’re not married. And that, for me was probably the most difficult process to go through it because she was the love of my life, she was the mother of my three children, we had met during the early recovery process and for me not to be able to save, “save her”, for me not to be able to steer her to a safe harbor. For me to experience the codependency that I subsequently learned, I also suffer with. Which you don’t find in Broken necessarily, for me for the story not to end the way it ended in Broken or the way that I would want it to end. That has been, that was very difficult for me, very painful for me. And you know, that’s why I’m a double winner today. You know, I don’t say that in Broken, because Broken came out in ‘06 and Alison and I separated shortly thereafter. And we were divorced, I can’t remember if it was ’08 or ’09. But the bottom line was that there was a whole other part of my story, which was about my coming to terms with the reality that I’m also a family member. And I suffered mightily, not in the case of, of substance use, but in the case of mental illness, and my powerlessness over it. So that was the most difficult part for me, Margaret.

Margaret 19:26

When you look at powerlessness over the people you love, it’s very evident when I talk to people who are in recovery with their own chemical addiction, mental health issues, behavioral addictions. They report until they get some clarity in their recovery, and sometime in the rooms they don’t truly understand the impact on their family.

William: Right.

Margaret: Would you a) agree with that and b) speak to whether Allison’s experience, and your powerlessness over that kind of brought it to deeper level of understanding.

20:02

William: Yeah, I don’t think I ever was in denial, candidly about the impact that my use had on the people that mattered to me, and the people that loved me and I loved. I mean I that it was pretty apparent, I left a lot of wreckage behind when I left New York to come out to treatment in Minnesota in 1989. I left a lot of bruises on the hearts and souls of the people that loved me when I continued to use, a relapse. And, you know, I damaged Allison when I went back out in 1994. So I wasn’t in any denial about that, what I was mostly in denial about was my own inability to stop others from the same thing that I’ve been unable to stop in my own life. I used to always, candidly, Margaret, I used to always think that the most difficult thing in my life was to let go of substances, right? Yeah. To surrender to the fact that I’m powerless over alcohol and other drugs, I used to think that was the most difficult thing to do. I mean, I couldn’t do it. I’d do it and go to treatment and pick up again, back and forth. And then in 94, I did let go of it. What? Well, that’s hard, don’t get me wrong, that’s hard. But what I learned is, it’s much harder to let go of other people, for sure. In those dynamics, including, especially those that I care for, those that I love, and those that I could swear I can save, you know.

And so I sort of came to, to that realization much later on. And I didn’t come to it because of a substance use issue. I came to it because, well, let me just tell you. In 2007, or 2008, I started going to Al-Anon to fix my marriage and fix my wife. Right? Those are noble causes, right? I’m going to go to Al-Anon in St. Paul, where I live, to fix my marriage and fix my wife. And what I discovered was, that while I failed at both of those, (laughter) I didn’t fix my marriage, and I didn’t fix my wife. What I learned in that experience is that the only thing that I can fix is me, to the extent that I’m still fixable, and I am fixable, we all are fixable, we can all be, get to be better people, even though we’re still imperfect. And that was eye opening for me.

Later on, I would learn that same principle, that same approach as it relates to my own children. And so that’s another story. But But yeah, I mean, I knew the damage I had caused. I did not realize how damaging that powerlessness over people could be for somebody like me until I figured it out. And I figured it out in a very painful way. I hit bottom stone cold sober in 2008.

Margaret 22:50

Yep.

William: Mmm.

Margaret: And I think also you speak to the pain of a person who doesn’t have a substance use disorder who is witnessing someone on that path and the pain of powerlessness, of not being able to do a damn thing about it. You can love them; you can offer them help. But at the end of the day, like you had to learn you had no power to change Allison.

Outro: William offers so much clarity and evidence of addiction being a family disease. If you have not had the opportunity to read his book Broken, I highly recommend it. William will be back with us again next week where we will go further into his story of his substance use disorder and family recovery.

Recovery is full of layers.

I want to thank my guest for their courage and vulnerability and sharing parts of their story. Please find resources on my website.

embracefamilyrecovery.com

This is Margaret Swift Thompson.

Until next time, please take care of you!