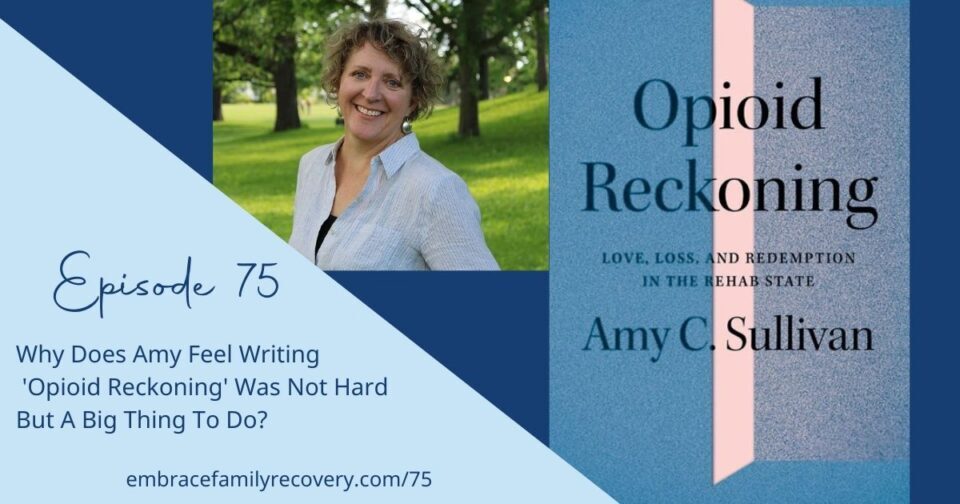

All of us who have loved someone with the disease of addiction know the struggle regarding the stigma surrounding this disease. Amy C. Sullivan, mother of a daughter with a substance use disorder and author of ‘Opioid Reckoning Love Loss and Redemption in the Rehab State,’ is joining us to share more about her recovery journey and the journey of writing her powerful book.

It is beautiful and tragic that Amy interviewed over 50 people to learn more about the history of drugs, addiction, and recovery.

The resources Amy highlights in this episode can be found in my show notes.

Exciting news, Amy’s publisher has arranged for a 30% discount when you order ‘Opioid Reckoning’ at http://z.umn.edu/OpioidReckoning using the promo code MN89780.

This offer is good through Dec. 1, 2022.

See full transcript below.

00:01

You’re listening to The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast, a place for real conversations with people who love someone with the disease of addiction. Now here is your host, Margaret Swift Thompson. The embrace family recovery podcast

Intro: Welcome back! Today, Amy C. Sullivan, author of ‘Opioid Reckoning Love, Loss and Redemption in the Rehab State’ shares more about her journey of writing this thought-provoking book. Amy shares some about the people she features in her book and how all her research has been a humbling and big journey to understand this powerful, cunning, and baffling disease called addiction.

Margaret 01:15

Your approach to the book was let me think outside the box and gather all the information I can to understand what I’ve been living; makes sense that you would find yourself in a meeting that fit your needs was inclusive of alternative things.

Amy Sullivan 01:29

Yeah, well, we kind of created it that way I was there kind of at the beginning, there was just one meeting in our area. And there needed to be more and people were having to drive too far. And this one was new and was also very much based in opioid epidemic. And that also made it probably at one point, going around the room with 20 people there, 18 would be opioids. And then seven years later, it’s more meth than opioids. And I’m also watching it like as a historian, as a researcher, and also for my own, you know, I’m getting something out of it.

Margaret 02:09

That’s quite a dance to do it from one lens.

Amy Sullivan 02:13

Yeah. And that’s why I had to stop and take a moment to write my book because it got heavy, it’s heavy to listen to entire life stories, and then write about tragedy.

Margaret 02:21

When you talk about Nar-Anon and what you got, from what I love that you said that I think family members don’t always understand finding their way into some sort of support community, whether it be a 12-step based or a church based or wherever they find their people. Often going to look for somebody to tell them about how to understand their addicted person versus I’m here to talk about me and how to understand what I’m going through.

Amy Sullivan 02:48

Yes, yes, that’s so important. I mean, I think that was the key. Because if you are just constantly in the fix it, give me the answers mode, you’re not going to be able to see the impact, the negative consequences that being constantly in that hypervigilant, fix it, mode is doing to your body or doing to your brain. I think you probably remember, well, some of the examples in the chapter ‘About Mothers’, one mother even just wanted to take her own life because she couldn’t handle the idea of her daughter dying before she did. And just that desperation, I think that you get to at that point, it’s really good to have a community of people who can support you. And of course, yes, therapists are great. Therapists are often needed. But just having a laid-back moment of sharing and reading things that make you feel stronger and better. It’s priceless.

Margaret 03:48

I agree. And Amy, the reality is that I as a therapist, don’t live one phone call away. I’m now a coach. So, I get to be more involved that way, that my clients who work with me can call me. But the reality is, when I first landed in a 12 step meeting for families, I remember, literally sitting there going, what have I done? But over time, one of the most appreciating pieces for me was coming from a family of people who told you what to do, how to do it, fix it, strong willed to a place where I could say what I had to say, and not get told what to do. Just unconditional, positive regard was astounding to me.

Amy Sullivan 04:30

Yes, yes. Yes. Carl Rogers. Yes, yes.

Margaret 04:34

And so, I love that that was similar for you.

Amy Sullivan 04:36

Mm. Yeah.

Margaret 04:39

When you made the decision to write the book, was it difficult? Was it a hard thing to consider doing?

Amy Sullivan 04:45

It was a big thing to consider doing. I had interviewed over 50 people. And in my process of interviewing them, I learned about the history of drugs, addiction and recovery that I didn’t know.

I think the hard thing was deciding which of those 50 long form stories were going to be used and what was going to be representative and essential. And I also spent a couple of years very deliberately and intentionally trying to find voices from communities that are often underrepresented. And in those underrepresented communities, what I encountered was some willingness to participate. But also, as a scholar, I understand the history of extractive knowledge where people come to a community that does not have a lot of privileges, or power in our culture, and take their stories and then use them in their own work. And that was something I did not want to do.

For instance, I want to give an incredible debt of regard and gratitude for the White Earth Nation in Minnesota, who have taken on a horrendous opioid epidemic in their community. So, if it were on a map, just by itself, it would just be this just raging red ball in the state of Minnesota.

Margaret: Wow!

Amy: When it gets washed out with white people, it doesn’t look like Minnesota has a problem. But people in the indigenous nations that we have in Minnesota, particularly White Earth have done unbelievable work for harm reduction, for diseases like HIV, Hep C, the highly transmittable diseases that happen with drug addiction. And with using their culture, using their community strengths, creating programs that are really set up for people in their community. And they’ve taken I would say, a very culturally informed and community-based approach. They’ve changed the landscape of care in Minnesota, I would say.

But however, I knew that even though I’d interviewed a few people, that maybe was not appropriate for me to use those stories.

And my other thing as a scholar, as an oral historian, is everyone who is in this book, they read how I wrote about them, and they read it in the final format. And they signed off on it. They said, yes, I’m fine with this, or yes, or would you change this. So, my approach is that way. And so, when it came time to try to reach back out to people, there were plenty of people I didn’t hear back from, and that’s okay. I ended up feeling peace with it. Because we all have to have the opportunity to agree with it, when our story is going to be out there. So, I think that was one of the biggest struggles for me.

The other was not having a similar lack of access to African American organizations that support recovery in the African American community. But I ultimately decided, you know, that’s not my story. And I should just stick with the amazing people that I have been able to reach out to.

One person I found really interesting interviewing is Yussuf Shafie. He has no history himself, but he became a social worker and decided he wanted to work with people who suffered from addiction. And he is of East African descent, started seeing a real big problem in the East African communities in Minnesota, and created his own treatment center for that community.

And what I found just really exciting about what he was doing is he was just facing stigma head on. And I think that that is something that we really need to think about is stigma. And his story in the book, I was just very excited to be able to include it because of the work he’s doing. And because of the newness of the East African communities in Minnesota, grappling with what are we going to do about this, when we say this is substances forbidden? Alcohol is forbidden, any drug use was forbidden. He’s like, yes, but then we have these people. So, what are we talking about here? We have to do something.

So, I tried to focus on innovators in my treatment chapter. People who are truly thinking outside the models and finding those places where they can provide more individualized care.

Margaret 09:32

So, when you say challenging stigma, can you share an example for the audience on ways because I know many family members feel isolated and stigmatized around addiction in general, but then adding on the layer if you lose your loved one, there’s a lot there and you go into it in the book in a very beautiful and respectful way.

Amy: Thank you.

Margaret: When you talk about Yussuf, what ways was he challenging the stigma or facing the stigma?

Amy Sullivan 10:00

He was bringing it out into the open. He was saying, we’re not going to hide from this, it’s not acceptable to just reject and kick out your family member. We say we don’t believe these things but look around you. These are stories. And these are happenings. And this is a crisis that we need to address in our community. And the only way that you get rid of the stigma is by talking about it. And by pointing it out, and by showing people no, that is stigmatizing that makes that person feel shame, or that behavior or that rule in the law even. Or that rule for this treatment center, you know, being kicked out or whatever. Those things are stigmatizing and cause harm. And where I think we need to address stigma right away is where’s it causing harm? Where’s it causing the most harm right now? And, unfortunately, we’re paying a really big price for a lot of these rules that no longer serve us. Like I think in particular about housing. And that was one thing that Yussuf talked about. He immediately saw that, okay, well, if I’m going to have these guys come and be in my treatment center, where are they going to go, 28 days later.

Margaret: Right.

Amy: And they had nowhere to go, because many times their families did not want them in their homes. So where were they going to go? They needed housing, and okay, yes, sober housing, fine. But sober housing often doesn’t, in the Minnesota model, accommodate relapses or slips? You’re out? And where’s that in between space? When do we acknowledge that that is part of someone’s recovery journey? And when do we say no, you just want to actually just keep doing drugs forever. That really wasn’t a slip.

11:47

This podcast is made possible by listeners like you.

Bumper: Boy, have I got a surprise for my loyal listeners you get a coupon for 30% off of opioid reckoning when you order at z.umn.edu/opioidreckoning using the promo code capital M as in Margaret capital N as in Nancy 89780

This is an offer for the listeners of The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast, and it is good through December 1st, 2022.

I wanna thank Amy Sullivan and her publisher for giving this coupon to you all. Don’t worry, I know it’s a lot! I got you, find the coupon and information on purchasing the book on my webpage embracefamilyrecovery.com

Look for the episode of the podcast you’re listening to, in the show notes below I will have all the details.

Take care of you!

13:06

You’re listening to The Embrace Family Recovery Podcast. Can you relate to what you’re hearing, never miss a show by hitting the subscribe button. Now back to the show.

Amy Sullivan 13:18

So, we need more nuance in these ways. And I think that thinking about housing in particular, and the number of people who are unhoused who have addiction, we have to figure this out.

There’s a great example in Duluth, New San Marco House, and they call it a wet house. And I know it causes a lot of uproar in certain sectors. But the truth is, if someone has shelter, and access to water and food, they are very much more likely to improve their life. If you are stuck on the streets, and you’re using, you want to just keep using because it’s terrible to be stuck on the streets. It seems like it’s the thing that’s eating itself, what’s it called an Ouroboros, the Dragon that’s got its tail on its mouth, and you just can’t break it apart.

Margaret 14:07

That’s good visual, actually. It’s a good visual, because when you’re in the journey with someone, it feels like that.

Amy: Yeah,

Margaret: on their side, but also on your side.

Amy Sullivan 14:16

So I dumped a lot on you right there.

Margaret 14:19

No, it’s a lot process. But what I would be curious to kind of dissect a little having worked in the treatment world where I have to care for, the collaboration of everyone. I have to work within risk factors, right. So, when someone’s bringing in substances to that center, there’s a risk to them, and there’s a risk to everyone else who’s vulnerable to relapse.

Amy: Absolutely.

Margaret: So, I understand that nuance. I also understand the nuance of harm reduction, and if somebody is not maintaining sobriety, but they can be in a place where they’re safe and not in the criminal element to survive. And there’s a world for that.

I also understand and sober housing, that there was a very slow increase of medicated assisted sober housing. You know, that took a while for them to be willing to help people who need medication through their recovery. So, it’s a very complex disease. You know, we say the solution is simple. Get abstinent.

Amy: Yeah. Yeah.

Margaret: If it were that easy, I’d be out of a job happily.

Amy Sullivan 15:24

Right. Right, right. It’s not.

Margaret 15:25

Yeah. So, I don’t know the answers. And I’m curious after doing all the research you did and all of what you’ve experienced through the stories in your personal journey, do you see solutions that make sense that are different than what are being offered?

Amy Sullivan 15:39

Well, I would say, what I got from the narratives, and the research I did is that the treatments that we have, have been siloed from each other. They’re judged. There’s judgment on the side of the AA, Minnesota model about medication. And there’s judgment on the side of medication about the AA model. And both sides have extremely legitimate concerns. However, the moral model of the 12-step program needs to stay within that context. And the science of addiction needs to be more deeply understood and more available to people. Because you do need community, when you’re in recovery, you do need a support network, you do need new places to live, you do need to get away from where you were. So, all of those things. I’m not dissing sober housing or anything, it’s just, to me, what I learned is we need to open our eyes and withhold judgment and create things that are judgment free, but yet have boundaries and consequences. If you can’t work in this system, then maybe you need to do this, not just kicking people out of institutions.

The damage that has happened as a result of not having access to the right kind of care, the lives lost. And we haven’t even touched on the drug war, which maybe I’m not equipped to do that, today. But the determination to keep doing the same thing over and over again, even when it’s not working, is the part that we have to stop, we have to stop that cycle. And if someone’s loved one has been in treatment more than two or three times, and it hasn’t worked, then you should try something else. Because that’s not going to work. And nobody wants to hear that. But knowing that there are young people who went to treatment like Spencer Johnson, 15 times. His mother lost count and never got the right kind of care. And he came from a suburban family in Minnesota, with resources like, that he died. It’s such an obvious, glaring problem. And that’s where I feel like we need a radical response to this, and not the little piecemeal here, we’re going to do this. And then we’re gonna, when you and I were talking earlier, before we started recording about all the settlement money. Are we going to take this opportunity to do something to end the opioid epidemic? Or are we just going to dish all that money out to a million different organizations and just hope that, you know, they’ll just keep doing what they’re doing? Or are we going to really think about new ways to combine some of these things.

And you know, the fact that I get it sober houses, they can’t be dealing with people who are using, but we also shouldn’t be just putting those people out. There needs to be more steps, more options, more places. And I’m not a public health expert. I’m not an addiction treatment specialist. But it just seemed to me that when you need a spot in a bed, you should get it. Because if you walked into that, er and you were having a heart pain, they would not kick you out and say go come back tomorrow or come back in 10 days, or we’ll call you. We’re at like these death moments.

Margaret 19:01

I do understand. And I also have the lens of being in the treatment world for a very long time where I’ve seen the other side of it where I can honestly say in every case, unless a client walked out against staff advice, they were given referrals, they were not just dropped,

Amy: right,

Margaret: many didn’t take it. Which what can you do if somebody’s refusing to take the care options?

Amy: Right, right, right.

Margaret: Is the system broken? Is there absolutely fragments of it that we need to address? Hands down? I like the concept of how do we pull the best of this with the best of this and work together?

Amy: Right? Right.

Margaret: To me, that’s the win.

Amy Sullivan 19:43

Yeah, we need to get out of the silos. And that was my first part. And I see hope in that I see hope in the way that principles of harm reduction have taken off. I feature that in my book as well. We need to protect people as much as we can knowing that we have things that we cannot control, we don’t seem to be able to control the inflow of drugs, and we can’t seem to control people having access to them.

So last December, I got an email from a young woman in Boston, who wrote to me through my college account, and said that she’d read an article about my book. And she said, I’m an unwilling fentanyl user. She referred to herself as an addict. And she was just affirming the myriad approaches that I was talking about, and we ended up emailing back and forth. I sent her my book. She’s 34, and she’s lived in hotels and motels, for most of the last 10 years. She experienced trafficking, sex trafficking. She experienced a severe amount of trauma in her life, and yet has a father who continued to keep her housed in hotels and motels. We started talking on the phone. And then shortly after that, I had lunch with Emily Bruner, who is the doctor featured in my book, I’d forgotten that she had gone to school in Boston. And she’s like, oh, Amy, I was telling her this story about the same woman, and she goes, Oh, you know what she should call this place called the Bridge Clinic. It’s at Mass General. She got me the number she gave me the name. I sent it on to my new friend. She went there.

So, the thing that this young woman was most worried about, was going back to detox because of how horrible those places are, when you don’t have any money, and how painful it is to get off of fentanyl.

The Bridge Clinic has a program where they gave her micro doses of Suboxone as she continued to use and then the doses went up and her use went down. And then before you know it, she wasn’t using, and she wasn’t craving, and she experienced no pain. She went there she had access to social worker, a psychologist, a psychiatrist, and a medical doctor. She’s eight months now.

Margaret: Awesome.

Amy: She probably been to treatment 15 times all over the country. Her father just did not want to give up on her. But I think at some point, he reached his limit. And what I’ve discovered in her is, she’s a writer, she’s a reader. She wants to help other women, she wants to, she’s such a gifted human being and when I think about those lives that are just wasting away on the streets or in these hotels where a lot of people apparently live which I was also unaware of. We can’t afford to keep losing all this precious capital. Right, and all these people and I think that Bridge Clinic is this incredible example of using medicine, but also providing the supports emotional, social, psychological supports that people need. Because you know, fentanyl that stuff is, it’s all tough, but that’s the new wave is the fentanyl wave that started in 2016.

Outro: I love to be challenged and shown different lenses through which to look at issues. This episode and Amy’s book ‘Opioid Reckoning Love Loss and Redemption in the Rehab State definitely did this. I am a believer in the Minnesota Model as it has saved my life and many, many lives I’ve witnessed. However, I am not arrogant enough to ever believe that it is the only way and the only solution to this disease of addiction. Please come back next week where we go further on this challenging topic of the need for more resources for people with substance use disorder in America.

Margaret 24:05

I want to thank my guest for their courage and vulnerability and sharing parts of their story. Please find resources on my website:

This is Margaret Swift Thompson.

Until next time, please take care of you!